Sioux War of 1862

|

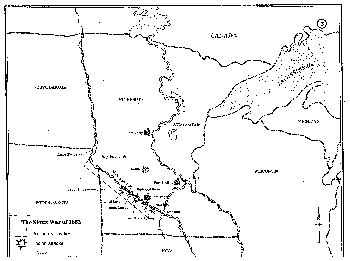

The Sioux War of 1862  By 1862, the Santee Sioux had given up their traditional homelands, which comprised most of southern Minnesota, in exchange for a narrow reservation on the southern bank of the Minnesota River. As compensation for their lands, the Sioux were to receive cash annuities and supplies that would enable them to live without the resources from their traditional hunting grounds. Because of administrative delays, however, both the cash and food had not arrived by the summer of 1862. Crop failures the previous fall made the late food delivery particularly distressing to the Indians. Encroachment by settlers on reservation land and the unfair practices of many American traders also fueled Sioux suspicions and hatred. Furthermore, the Sioux were emboldened by the Minnesotans' relative weakness, brought on by the departure of many of their young men to fight in the U.S. Civil War. This combination of hunger, hatred, and the perceived weakness of the Minnesotans and the local military created an explosive situation that needed only a spark to bring on a full-scale war. The spark came on 17 August 1862, when four Sioux warriors murdered five settlers near Acton, Minnesota. On 18 August, Indians at the Lower Sioux Agency rebelled, killing most of the settlers on their reservation. A few escapees managed to reach Fort Ridgely and warn its commander, Captain John S. Marsh, of the rebellion. Marsh and forty-seven men subsequently sortied from the fort only to be ambushed at Redwood Ferry, where half of them, including Marsh, were killed. Twenty-four soldiers managed to return to Fort Ridgely. News of the rebellion spread quickly through the settler and Indian communities. For the Sioux, this was a catharsis of violence; for the settlers, a nightmare had come true. Most settlers in the Minnesota River Valley had no experience with warring Indians. Those who did not flee to a fort or defended settlement fast enough were at the Indians' mercy. The Sioux killed most of the settlers they encountered but often made captives of the women and children. In response, the Army marshaled its available strength, 180 men, at Fort Ridgely, where well-sited artillery helped the soldiers fend off two Sioux attacks. At the town of New Ulm, which became a magnet for settlers fleeing the rebellion, defenders also repulsed two Indian attacks. The stout resistance of the settlers and soldiers effectively halted the spread of the rebellion. Now, the military seized the initiative. A relief expedition under Colonel Henry H. Sibley arrived at Fort Ridgely on 27 August 1862. Sibley's command consisted largely of green recruits with second-rate weapons. The Sioux surprised and inflicted a tactical defeat on Sibley's men at Birch Coulee on 2 September. This minor setback, however, did not change the course of the campaign. From 2 to 18 September, Sibley drilled his soldiers and received supplies and reinforcements, including 240 veterans of the 3d Minnesota Infantry Regiment. On 19 September, Sibley resumed his advance. This time, the expedition encountered and defeated the Sioux at Wood Lake on 23 September 1862. Three days later, the Sioux released their 269 captives and surrendered, ending the campaign. Outraged over the uprising, state authorities executed thirty-eight Indian prisoners and banished the other captive Sioux to reservations outside Minnesota. In addition, the Army launched punitive expeditions into the Dakota Territory in 1863 and 1864 that drove the remaining bands of free Santee Sioux well away from Minnesota's western border. Two years later, along the Bozeman Trail, the U.S. Army would fight another branch of the Sioux nation, but this time with very different results. Source:

Links:

|